Why Coaching is the Key to Adaptability and Resilience

Why can some individuals, teams and organizations thrive in unpredictability and adapt quickly to changes while others became stuck, resolutely ignoring the need for change, resisting change ‘initiatives’, sabotaging themselves and their organizations? The answer doesn’t lie in clever change process planning, or meticulous execution but in something much simpler: the quality and focus of their relationships and conversations.

As a species, we humans are relatively adaptable to changes in our environment. We wouldn’t be at the top of the food chain and dominating our environment (for good and ill) if we were not. But the rapidity of change in our modern world means that we can easily find ourselves, our teams, and our organizations uncomfortably ‘badly adapted’. At that point, individuals will seek support, and organizations and leaders will respond with ‘transformation’ and ‘reorganization’, attempting to close the gaps that they have allowed to open up.

But whether at work or in our personal lives, managing adaptation through a stop-start series of forced transformations is wasteful. Much better to ‘build adaptability in’, to move through a series of small, timely shifts that keep us well adapted than to allow an uncomfortable ‘adaptation gap’ to build up.

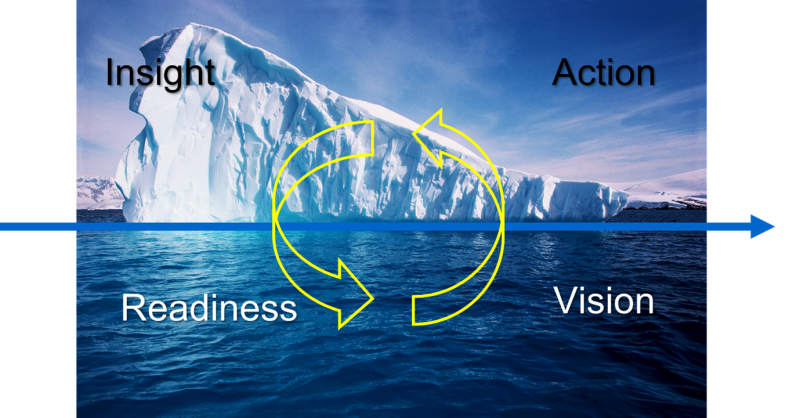

As an individual, having coaching or mentoring conversations and adopting a coaching philosophy supports you in remaining well adapted in this way. In a group, team, community or organization, a coaching leadership style and culture builds the relationships and supports the conversations that enable adaptability. But why? How does that work? The diagram below presents a cycle of adaptation that is based on the one developed by Dr Mike ‘The Mentor’ Munro Turner, to show this ‘constant learning’ in action. It appears as an ‘iceberg’ because everything below the line happens ‘inside’ an individual and may be difficult to observe.

Coaching conversations and relationships speed and lubricate this cycle in a number of ways:

- Creating Deeper Insight - By encouraging us to reflect, and challenge our assumptions, coaching helps us to real Insight. We see ‘reality’: what is, and not what we assumed was there.

- Building Readiness to Adapt - By helping us to deeper self-awareness, coaching allows us to face the fears and beliefs that might keep us in a badly adapted present and allows us to move forward.

- Developing Authentic Vision - By giving us the space, support, and challenge to focus on the future we are creating, we can develop a personal and genuine vision of what it is (and how it is) that we need.

- Taking Action to Adapt - By supporting us in building new habits of thinking, feeling, and acting, we can bring that vision into reality.

We seem to share a hopeful delusion that understanding a possible advantageous change is enough to change our habitual responses, despite our experience that in many cases this is not true. Coaching conversations support our ability to learn from experience by providing support for a reflective process. As John Dewey said, ‘we do not learn from experience… we learn from reflecting on experience’. But experience and insight are not always enough to support sustainable adaptation. How often have you had the experience, for example, of realizing that changing a habit such as more regular exercise would be beneficial for you, signing up for an exercise class or to the gym, and then finding yourself three months later in exactly the same habits as you were before you had that realization?

Coaching conversations and supportive coaching relationships deepen self-awareness and help us to deal with limiting fears and assumptions. They can enable us to envision ‘how will I be different’ in the detail that we need to put change into practice. Paying regular attention to these ‘below the waterline’ elements of the cycle of adaptation is key to freeing us up to change. But the capacity to take effective action and adapt our habits is also a key component of creating adaptability. And it is all too often ignored by leaders, managers and even by coaches and mentors.

There is an increasingly good neuroscientific basis for this way of thinking. Our current habits of response are laid down as well-used neural pathways in our brain. We have a habit of responding to particular situations or triggers in terms of thinking, feeling or acting. These habits happen before we have had time to ‘engage’ our conscious mind to consider whether or not they are the response we choose, whether they are consistent with the person we want to be, or whether they are effective and well adapted to our environment.

A lot of what we do is a simple response to our environment. Helping others to shape their environment to support positive adaptations and recognise what it is in their environment that triggers old habits that keep them ‘stuck’, is a really important element of coaching for adaptability. In neuro-scientific terms, we are trying to build a new neural pathway that, with enough practice, will become a helpful new habit.

So what can we do to get that new habit working? We need two key things: a plan and rewards.

We need a plan because this is a new thing, it needs to be practised and if we don’t think it through in detail and make the time and opportunity to practise, it just won’t happen. And a plan means knowing what, when, where, and how. But practice is hard. We won’t get it right every time. And habits get built upon an expectation of rewards, and the reason they form is that we have at some point experienced repeated positive responses for that behaviour. Our brains not only learn to expect rewards; they actually start to manufacture a reward in the form of a ‘feel good’ neurochemical response when we do something habitually. (Sneaky huh?)

Unfortunately, a lot of the habits we want to build are difficult to form because the rewards will come later. So if we want to establish a new habit, we need to harness our brains by building an immediate reward, some way of making ourselves feel good right there, even if it is hard and doesn’t work every time. After a while, when the habit is formed, we won’t need the conscious effort of practice and we won’t need that reward.

Just measuring progress, giving yourself a ‘tick’ or a ‘star’ every time we do the new habit can be a reward in itself. A leader who wanted to build better-balanced working habits, partly as an example to his team, put a jar with tokens on his desk every week. Every time he went for exercise, took a moving break between team calls or finished work early enough to spend some time with his family, he moved a token into a dish – aiming to empty it by the weekend. And if habits can be regularly practised, in response to a trigger that already exists in our environment, they get ingrained more quickly and easily.

If we can shape our environment to support new habits and practise them, then new habits can be built and maintained in a matter of weeks and months, rather than years. It doesn’t mean that the old ‘bad’ habits won’t ever appear again, especially if the environment changes. But once you’ve learnt how to alter your behaviour through retraining your habits, you can do it again and again. So coaching conversations and relationships that support habit change aren’t just helping people to change now, but also making them more ‘adaptable’ for the future.

A constant healthy adaptation that keeps us well-adjusted is vital, and as the speed and scale of the adaptations we need to make increases, so does the need to invest in building a coaching culture and leadership styles that support adaptability in organizations and communities. The impact of our coaching on adaptability will be highest when our coaching conversations focus on all aspects of the adaptation cycle including building new habits.